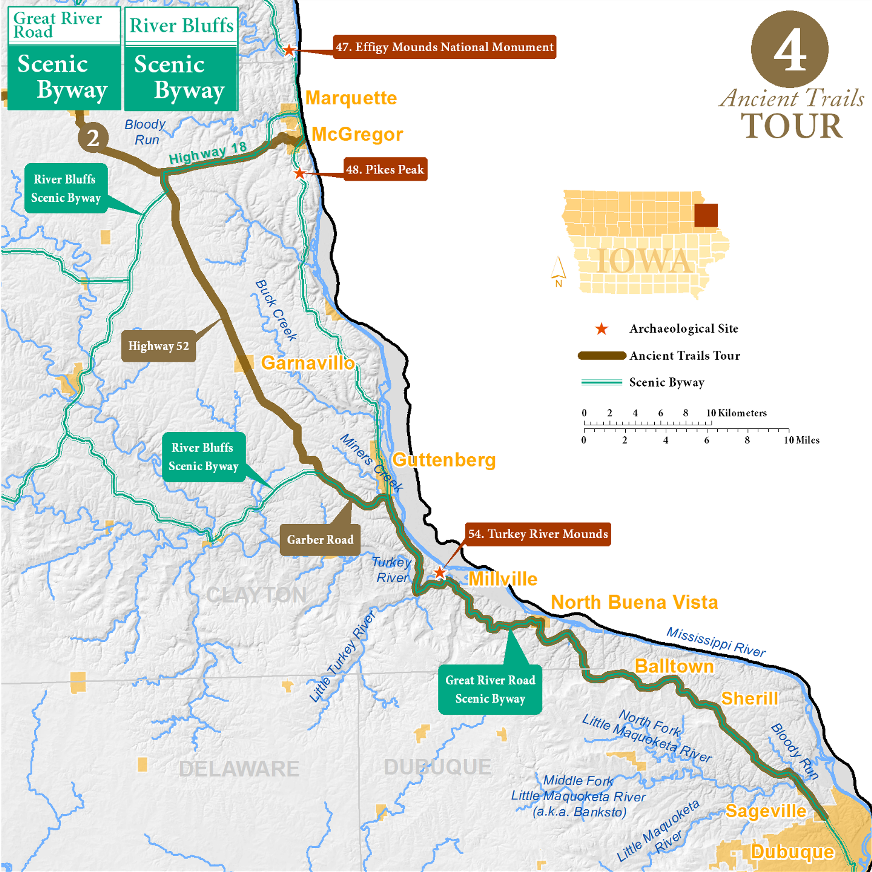

Dubuque to McGregor Tour

When settlers arrived in Dubuque, the largest town in northeast Iowa, they ascended the Couler valley to the Little Maquoketa River, from there they followed long upland ridgetops which parallel the Mississippi valley. Eventually this overland trek took them to the old Military Road, where they could turn right to go to Fort Crawford in Prairie du Chien or left to go to Fort Atkinson or St. Paul.

Couler Valley to the Little Maquoketa River (4 miles)

Couler valley is an odd geological formation. Very straight and steep-walled, it connects the Little Maquoketa valley to the Mississippi valley, several miles below the modern mouth of the Little Maquoketa. Geologists generally agree that the Little Maquoketa once flowed down Couler valley until it finally cut its modern valley to the Mississippi more than 10,000 years ago. It is also possible that the Couler was carved by an ancestor of the Mississippi River during the Pleistocene. This long passageway into the interior of Iowa was undoubtedly used long before American settlement. Pioneers recalled the valley was filled with corn fields planted by Indians.

The Little Maquoketa River runs through cliff-lined valley walls. U.S. 52 winds along this valley, but you will turn right on Sherill at the tiny hamlet of Sageville and ascend the bluff.

Little Maquoketa River to Turkey River (25 miles)

Early travelers on ancient trails often traveled along upland bluff tops; straighter and with fewer obstacles, they were the fastest routes. As you pass the town of Sherrill, notice the large hill on the left, the “Sherrill Mound” rises 200 feet above the landscape, its geology has not been studied in detail. This is the first of a series of isolated hills between Sherrill and Old Balltown, even though they are in the eroded Driftless Zone of Iowa, their tops are the same elevation as the glacial-filled landscapes to the west. After Sherrill you will follow Balltown Road along the Balltown Ridge. Turn right (north) along North Buena Vista Road which becomes the Great River Road. Cross Plum Creek and descend to the village of North Buena Vista. The Great River Road will take you along Hefel Ridge, and down to the Turkey River valley.

Turkey River to Girard (25 miles)

In the first decades of the 1800s, explorers such as Zebulon Pike noted Meskwaki villages near the mouth of the Turkey River. The Turkey River Mounds State Monument (Archaeological Guide to Iowa 54) overlooks the bluff at the mouth of the river. Follow U.S. 52 to Guttenberg with its beautiful limestone downtown. To stick with the ancient trail, follow Garber Road west up the bluffs, right on Leaf, right on Kale, and back to U.S. 52 north. This segment of U.S. 52 almost perfectly follows the GLO trail mapped in 1838, and the town of Garnavillo was laid out with its streets aligned to the ancient trail. The trail ends at U.S. 18, near the Girard tract, a large lot of land that extended east to Marquette, purchased by Basil Girard in 1795. Little is known of Girard, if he lived there or what he did with the land, but his tract is still indicated on official township maps.

Great River Road and River Bluffs Scenic Byways

This ancient trails tour shares the road with portions of both the Great River Road and the River Bluffs scenic byways. Click here for more about Iowa's scenic byways.

Archaeological Sites

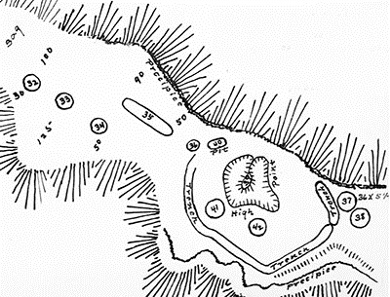

54. Turkey River Mounds

Encircled graves can be seen at the Turkey River mound group, 41 mounds on a bluff overlooking the mouth of the Turkey River. Most of the mounds are fairly typical Late Archaic to Late Woodland period graves, but two mounds stand out. Mound 37 contained a headless skeleton encircled by a ring of large limestone rocks. If those conducted the burial were superstitious, this person must have been very powerful; the ring either kept their spirit safe or enclosed their spirit.

Mound 38 contained at least 11 skeletons. One individual, also headless, was buried below a pile of rock slabs in the center of the mound. Buried with him were the remains of an adolescent and young child. To the southeast of the mound center were six individuals, four without heads, buried in a common pit. In addition to being headless, many of the skeletons showed evidence of violence that occurred at the time of death or post mortem. But these do not seem like the bodies of enemies: they were buried with care, sprinkled with ocher, and provided with grave goods.

This site raises more questions than it answers. Were the ditch and stone ring enclosures meant to contain the dead within, meant to protect the dead, or was there some other meaning? Why were so many of the dead headless? Were the heads removed by their families as ritual, as is known from some Indian accounts? Regardless, the burial site must have been an extremely potent location to whomever built it, laden with powers that, ultimately, only they understood.

47. Effigy Mounds National Monument

48. Pikes Peak - Mounds and the Unconstructed Fort

In 1805, Zebulon Pike set out to explore the Upper Mississippi; among his duties was to find a location suitable for a military fort near the mouth of the Wisconsin River, then the main trading artery linking the Mississippi River to the Great Lakes. Pike recommended a site situated on a high bluff, where the visibility of the delta and the village of Prairie du Chien was good, and nearly-vertical cliffs would offer protection.

The US Army opted instead to construct the fort, Fort Shelby, on Brisbois Island, closer to Prairie du Chien. This was revealed to be a foolish decision when, during the War of 1812, a small contingent of British and Indian allies were able to shell the fort into submission with ease. The United States lost control of the Upper Mississippi during the war.

The Pikes Peak bluff land was purchased by Alexander McGregor, and his grandniece Martha Buell Munn donated the property to the federal government in 1919, part of the earliest efforts to establish what would become Effigy Mound National Monument. Iowa received the land from the federal government in 1936.

While regrettable from a military standpoint, the lack of a fort on the bluffs helped to preserve a collection of mounds. Ellison Orr mapped 55 mounds in seven groups along the bluffs. Subsequent research during the 1970s determined that nearly all of the mounds mapped by Orr had been destroyed by looting, farming, and construction.

To Visit

Pike's Peak State Park is on the bluffs just south of McGregor. From McGregor, follow the Great River Road (Walton Street) south up the bluff to Pike's Peak Road. Follow the signs.